In a recent assignment for a Masters in Performance Coaching I was requested to develop a model of my coaching, which focuses on BCU type short 2 day courses and the episodic nature of these sessions. See below

My Coaching Process Model

Earlier in the semester I was challenged to construct out coaching role frame, in essence the boundaries in which I coach. Looking back to Figure 1, and as I construct the coaching model within that role frame, the complexes of the coaching process, coupled with the influence of the playing space and management of the environmental risks. Traditional sports are set by fixed boundaries and sets of game rules that defined the playing space.

Figure 1: My Coaching Role Frame

For white water kayaking, there is of course a physical boundary, yet the nature of the down river flow, means the show is always on the move, and as such the safety scope of coaching practice has considerable bearing on the coaching process. Risk management is of prime importance, especially as the coaching I undertake is normally on Class IV or more, on a difficult scale of I to VI with Class VI considered the limit of possibility. And although through implicitly managing the descent of the river, controlling outcomes is highly challenging when so much contributes to a successful descent. I attempt to orchestrate coaching venues to control the variables that directly affect the athlete, yet I can not be the captain of their ship, and as such minor mistakes in such a dynamic environment leads to occasional interventions. The personal inter play between the athlete and coach, has considerable context in the coaching process, shaping and forming outcomes, that may not been apparent in the initial goal setting.

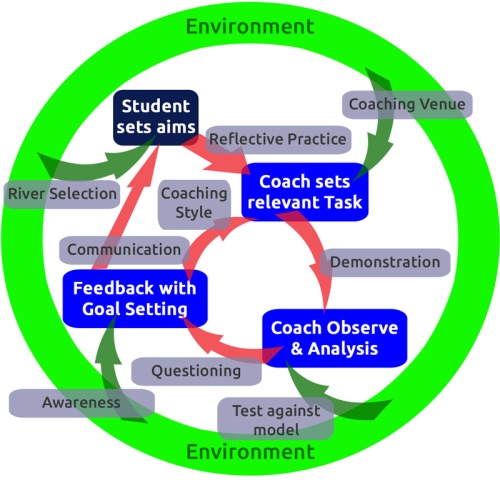

As much of the coaching practice is in principle problem solving, with a considerable environmental influence, the core of my coaching process model is based on Fair (1987). The short term episodic nature of the mainstay of my coaching, centres on both technical or tactic issues where the environment plays a significant part in each element of the coaching process. As such in Figure 2, the environment is both the boundary of the framework and a main contributor. Session’s framed by the students upfront aspirations, which allows the coach to set a task, based on reflective practice of previous solutions to similar athlete wants. Where the student wishes to go in terms of river or rapid selection, is often a main contributing factor as to what they wish to do. Within the UK’s temperate climate, the conditions for white water kayaking are not always abundant, students may wish for near ideal conditions, which in turn may prove challenging to get the session(s) off the ground in the first place.

Figure 2: Episodic White Water Kayaking Coaching Progress Model

Once the wants of the student have been presented and framed, similar sessions may be recalled to offer a set of tasks, again the environment conditions, will heavily influence as to where and what coaching venues are on offer and whether the students aspiration can even be met at such locations. Given the common episodic nature of the mainstay of short course white water kayak coaching, the initial tasks may test the athlete’s fundamentals rather than directly address their demands, as is often the case the coach may not of observed these student(s) before hand. Once the session is underway, the task is set, explanations of the rivers topography are given along with a demonstration. White water kayaking is made up a set of principal skills that blend both tactics and technique together, whilst descending down river. In the main, these skills are straight forward, yet the understanding of both gravity’s role and kayak/paddler’s momentum is often significant hurdle with the comprehension of what needs to be done. Hence the requirement for demonstrations, in addition to being the coach that is also in a kayak, the coaches other role is that of front line safety. Being a bank based coach, can work at selected coaching venues, yet it does not mean that all the possible rescue scenarios can be easily executed.

From the task, the coach can observe and analysis the athlete performance, and measure this against what should be happening. A rudimentary model of the skill’s application, should frame the performance analysis. Questioning of the student, may provide wider clarity of what they attempted to do, and their perception of what they actually did. This helps shape the feedback and the coaching comprehension of whether the student understands both the nature of the task, the elements at play to execute the task and the river environment in play. Awareness of specifics within the river environment is a key contributions to the feedback, and subsequence goal setting. Communicating the changes required to alter the performance, directly govern the coaching style applied, and may in turn change the student’s initial aims.

‘Good Practice’ can be admirably framed as anything that brings about repeatable consistent results. A students and coaches reflection and review sessions, can aid the changing of performance and be of benefit in the next session. The cyclical nature of the model, allows the setting of Practice Structure, which is important if the student is able to perform in an adapted manner in a changeable and variable environment. This can of course be challenging if the available resource, has limited venues, even more so when the river trip is linear in nature. And can often give the appearance that sessions may be delivered off the hoof, even the fine balancing acts of providing added value and a successful descent, may mean the pace and timing of the practise structure are morphed and applied at the appropriate venues, and not necessarily at the desirable moments.

Within the available literature there is little research in adventure sports coaching, and certainly no coaching process model on offer for white water kayaking. Cushion, Armour & Jones (2006) proposed that the coaching process is a dynamic activity which has at its core the environment, the student, the coach and the contextual relationships of all of these, rather than something which is delivered. There are several flaws in the model in Figure 2, the most noticeable is the lack of scope for longer term development, the short session focused cycling of the coaching process, lends little to developmental performance coaching. Unfortunately this is the nature of the market place at present, students budgets mean they search for quick fixes, tips if it were, to step on from the plateau they find themselves on.

There is little doubt, “A fundamental problem with coaching knowledge so far, and its accompanying ‘models’ approach, is that knowledge producers have not taken the time to adequately acknowledge and explore the complex nature of coaching before developing general explanations of and recommendations for ‘good practice’ (Strean, 1998). Oversimplification of the phenomenon and over-precision of prescriptions is the unfortunate price paid”, Jones & Wallace (2005). And although the coaching process model presented is based on episodic coaching sessions, the inputs and environment considerations could be of value to the community of white water kayaking coaches. Yet “coaches learn to live with the ambiguity inherent in coaching, and so render it relatively manageable.” Jones & Wallace (2005) and whilst the market place remains quick fix hungry, whether rightly or wrongly, there is little desire or worth to over-conceptualise coaching process for white water kayaking.

References

Chelladurai, P. (1993) Leadership, in: R. N. Singer, M. Murphy & L. K. Tennant (Eds) Handbook of research on sport psychology (New York, Macmillan), 647–671.

Côte ́, J., Salmela, J., Trudel, P., Baria, A. & Russell, S. (1995). The coaching model: a grounded assessment of expert gymnastic coaches’ knowledge, Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(1), 1-17.

Cushion, C.J., (2007). Modelling the Complexity of the Coaching Process: a Commentary – International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching – 2(4), 395-401, Brewer, B. pp. 411-413. Gilbert, W. pp. 417-418. Mallett, C. pp. 419-421.

Cushion, C.J., Armour, K.M., & Jones, R.L., (2006). Locating the coaching process in practice: models ‘for’ and ‘of’ coaching, Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 11:01, 83-99.

Fairs, J. R. (1987). The coaching process: the essence of coaching, Sports Coach, 11(1), 17–19.

Franks, I., Sinclair, G., Thomson, W. & Goodman, D. (1986) Analysis of the coaching process, Science, Periodical, Research Technology and Sport, 1, 1–12 (January).

Lyle,J. (2002). Sports Coaching Concepts: A Framework for coaches’ behaviour. London: Routledge.

Jones, R.L. & Wallace, M., (2005). Another bad day at the training ground- coping with ambiguity in the coaching context. Sport, Education and Society, 10 (1), 119-134.

Jones, R.L. & Wallace, M., (2006) The coach as ‘orchestrator’, in: Jones, R.L. The sports coach as educator: reconceptualising sports coaching. London: Routledge.

Mageau, G.A., & Vallerand, R.J. (2003). The coach-athlete relationship: A motivational model. Journal of Sport Sciences, 21, 883-904.

Mallett ,C. J. (2005). Self-Determination Theory- A Case Study of Evidence-Based Coaching. The Sport Psychologist, 2005, 19, 417-429

Smoll, F.L., & Smith, R.E. (1989). Leadership behaviors in sport: A theoretical model and

research paradigm. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 19, 1522-1551.

Strean, W. (1998). Possibilities for qualitative research in sports psychology, The Sport Psychologist, 12, 333/345.

Very good article! We are linking to this great post on our

site. Keep up the great writing.